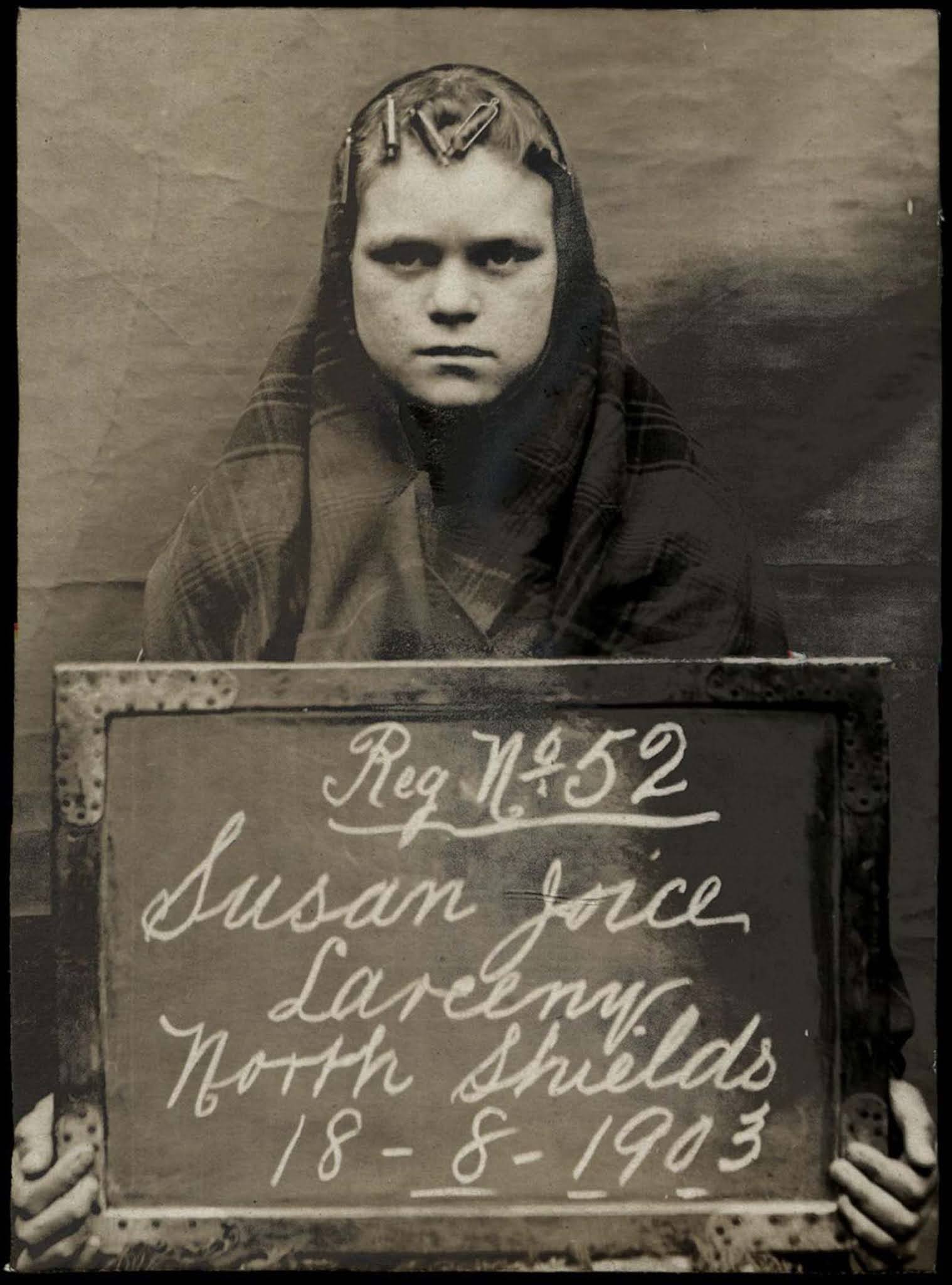

Susan Joice, 16, arrested for stealing money from a gas meter. 1903.

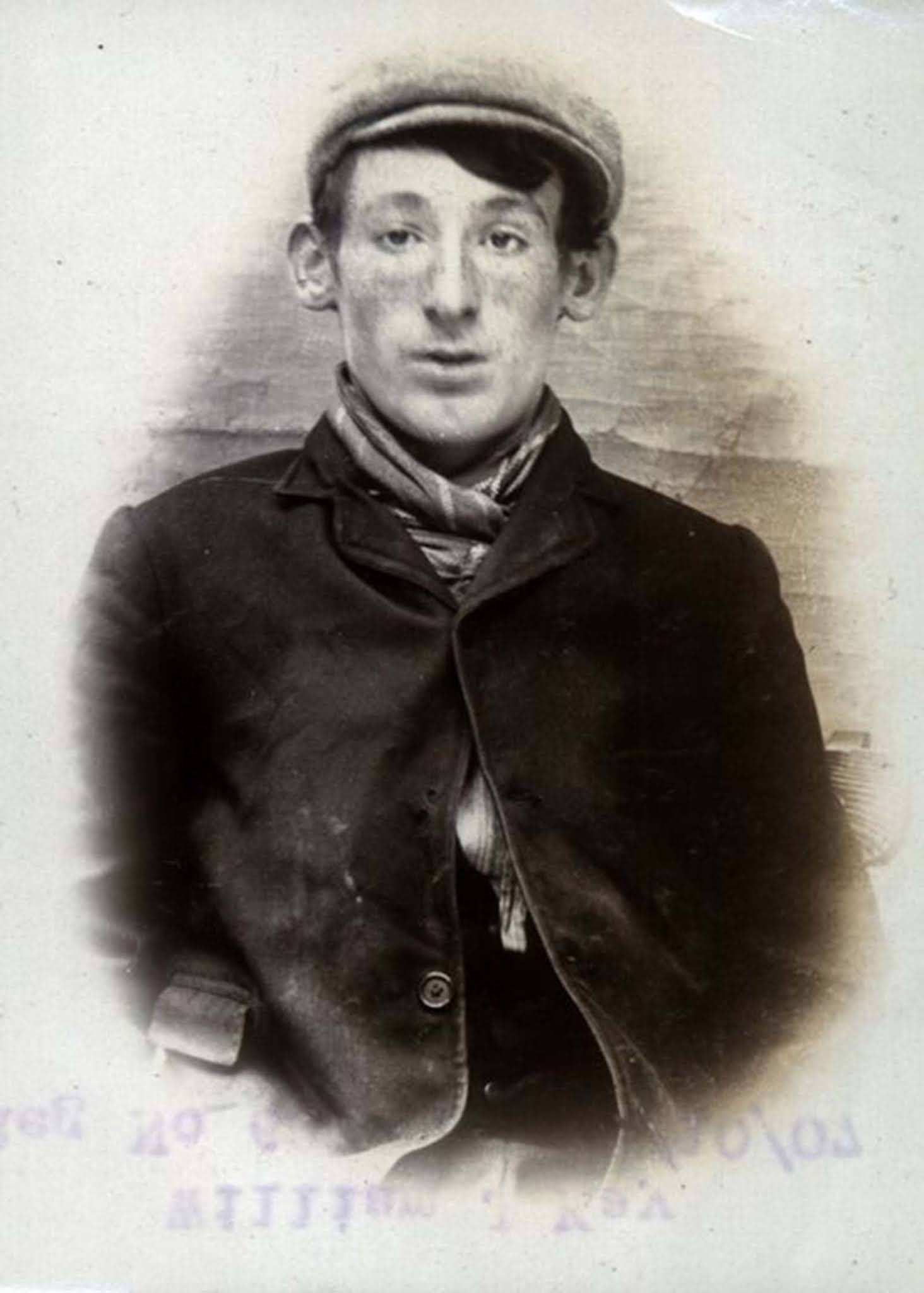

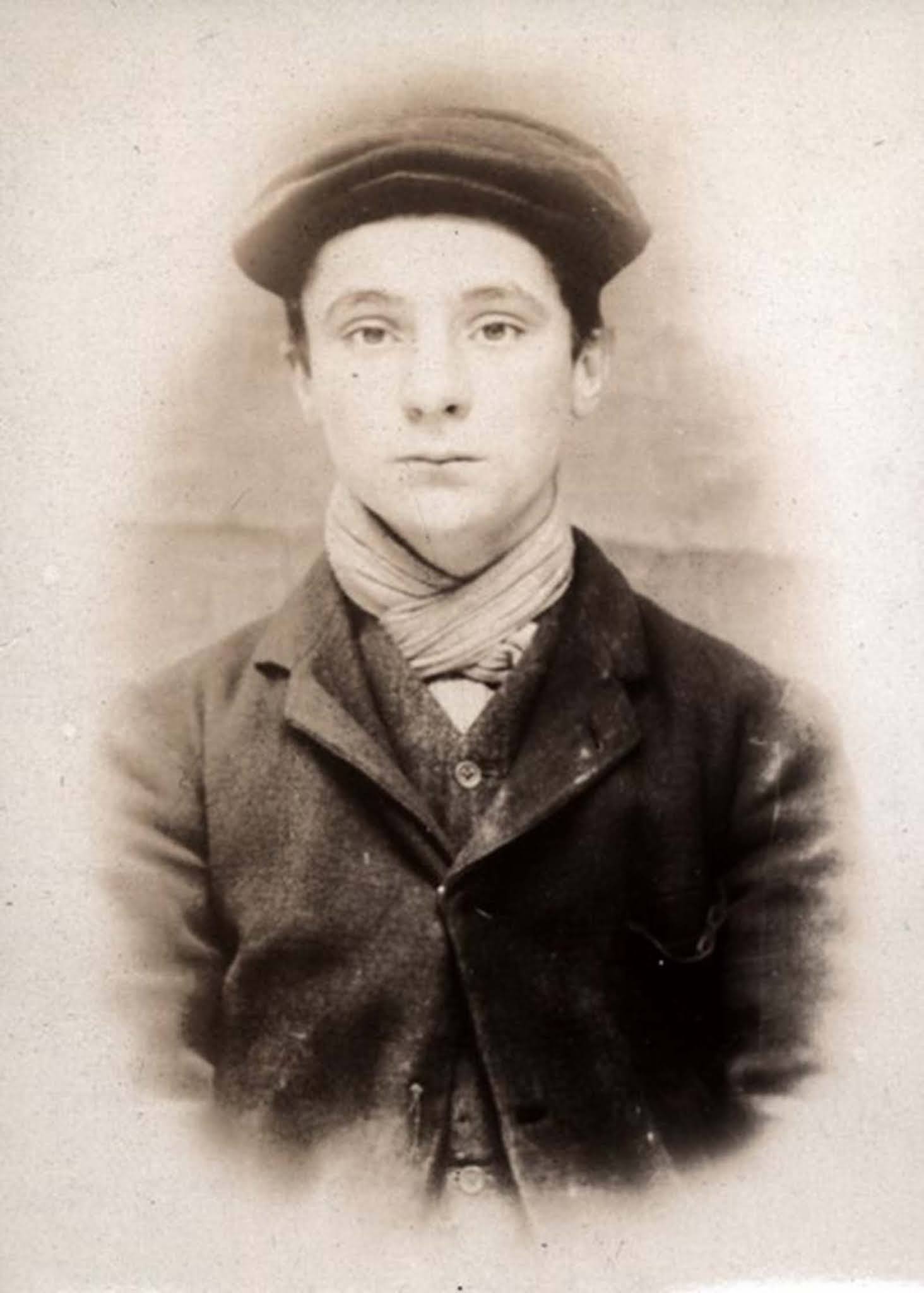

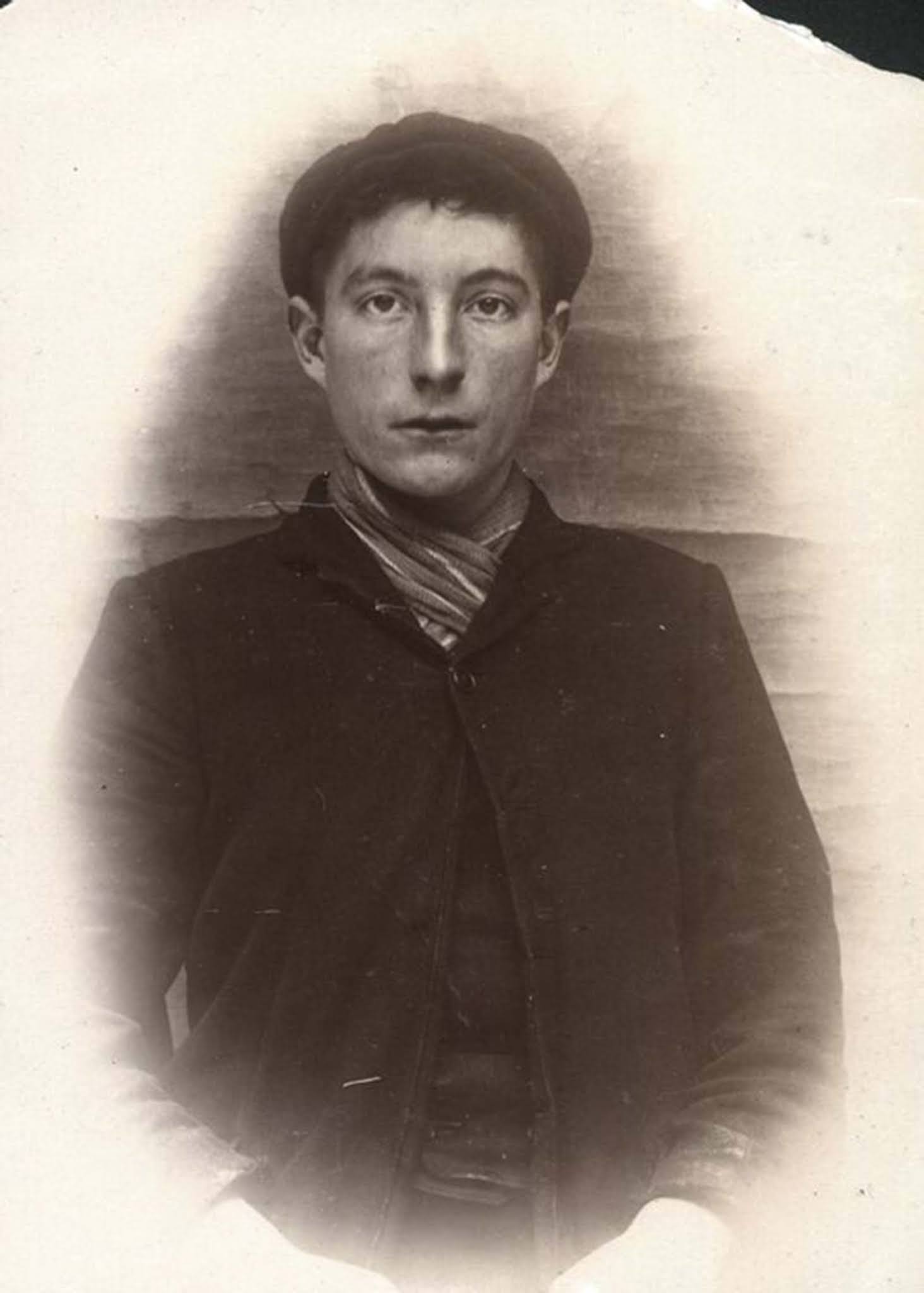

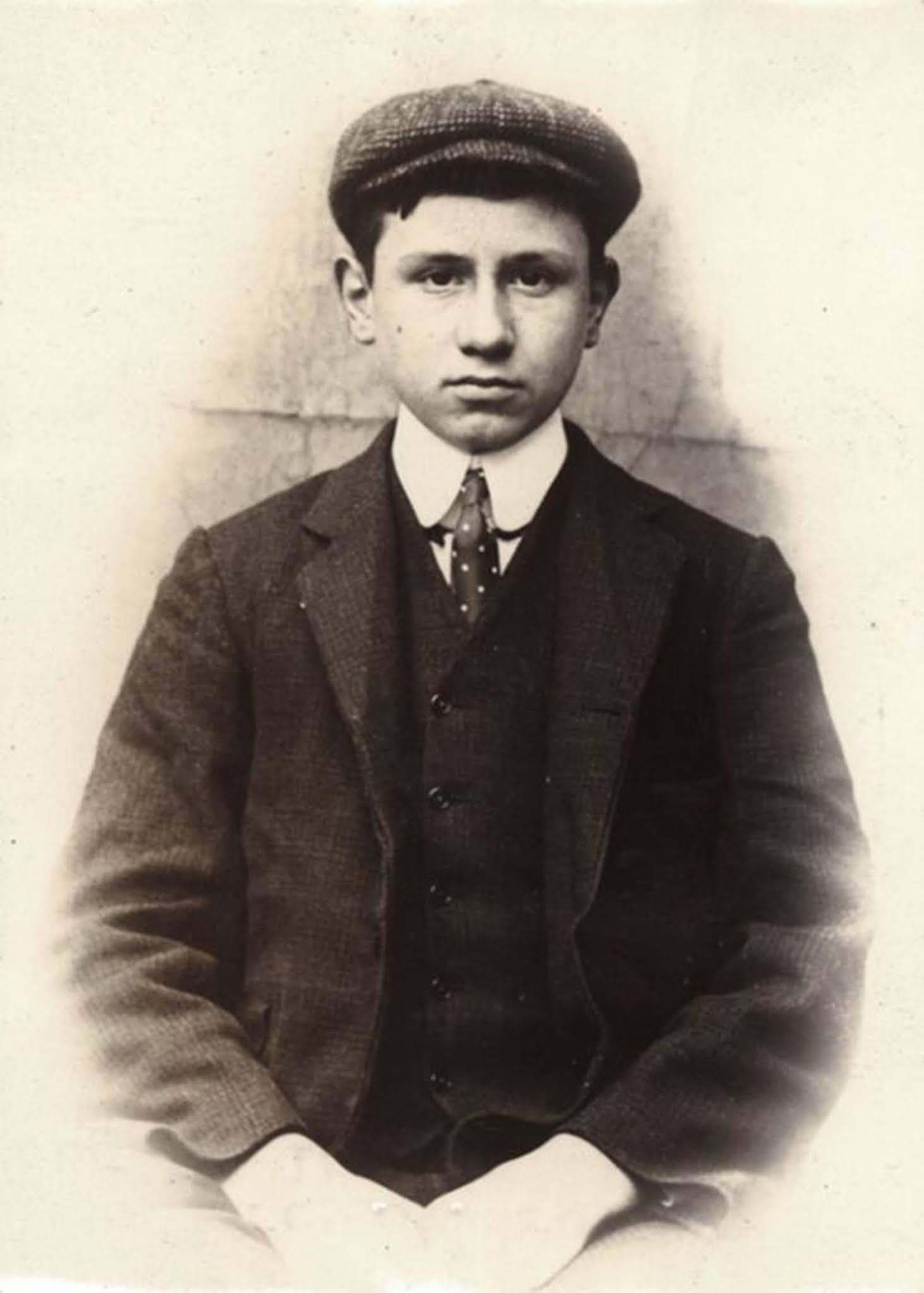

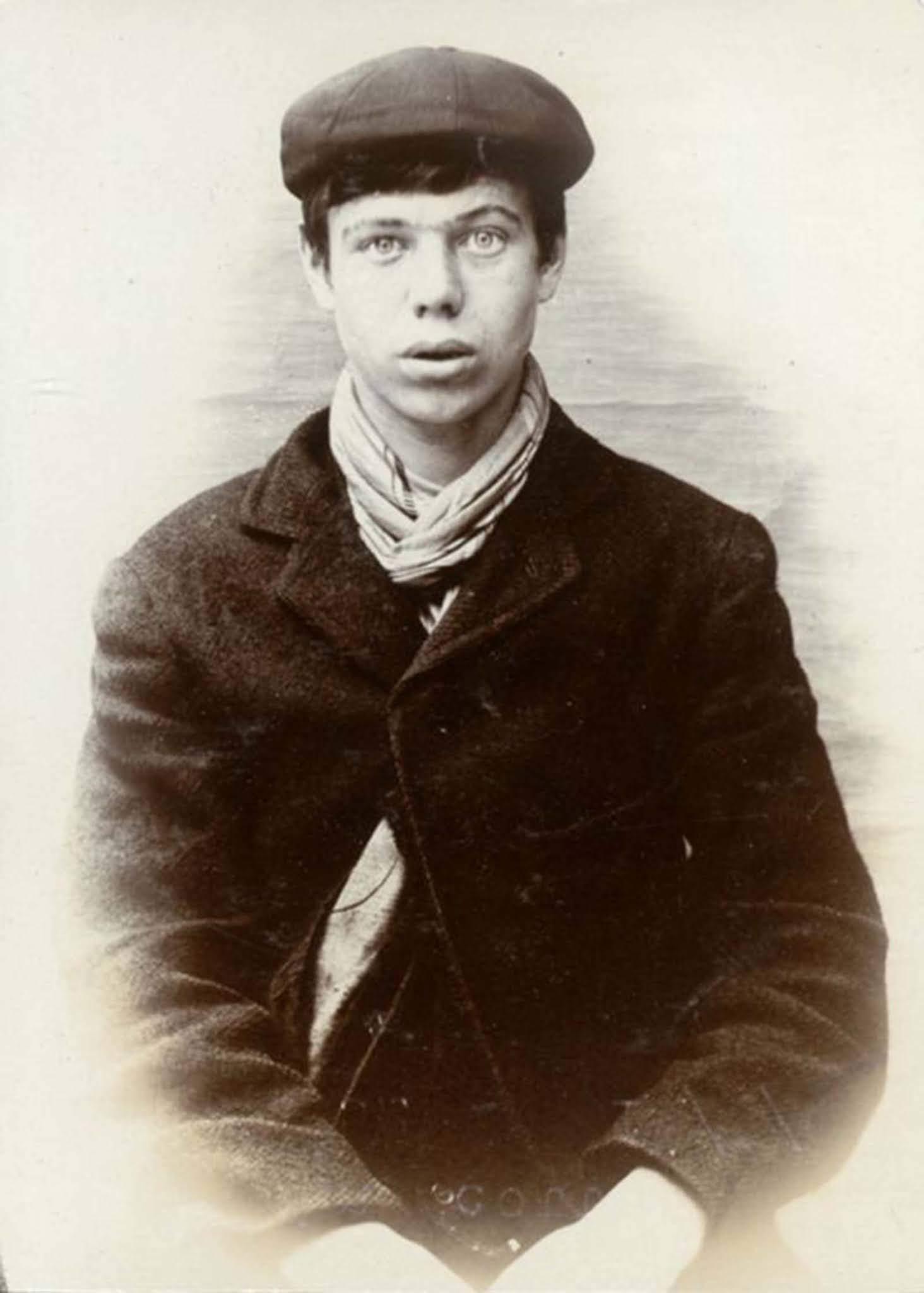

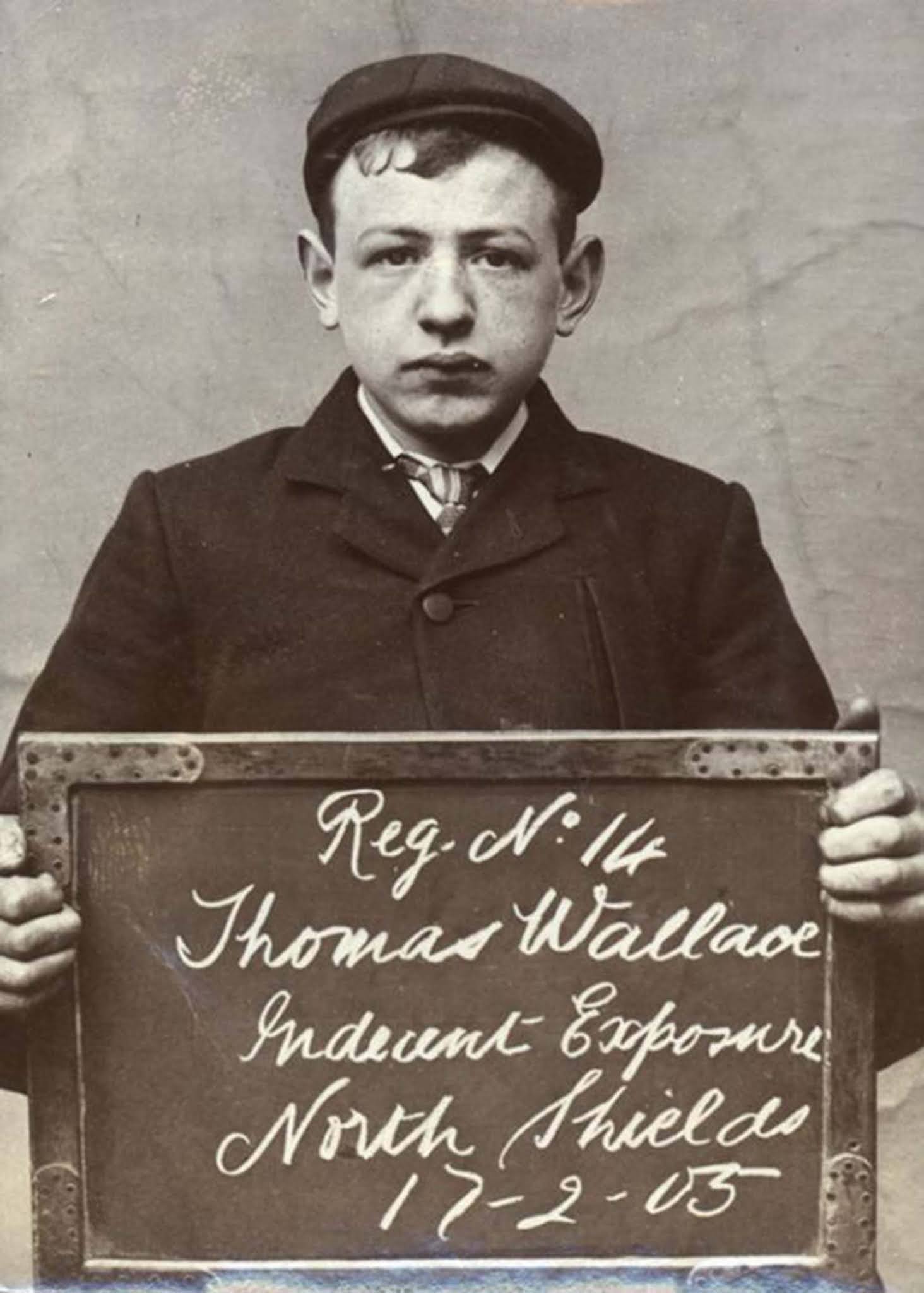

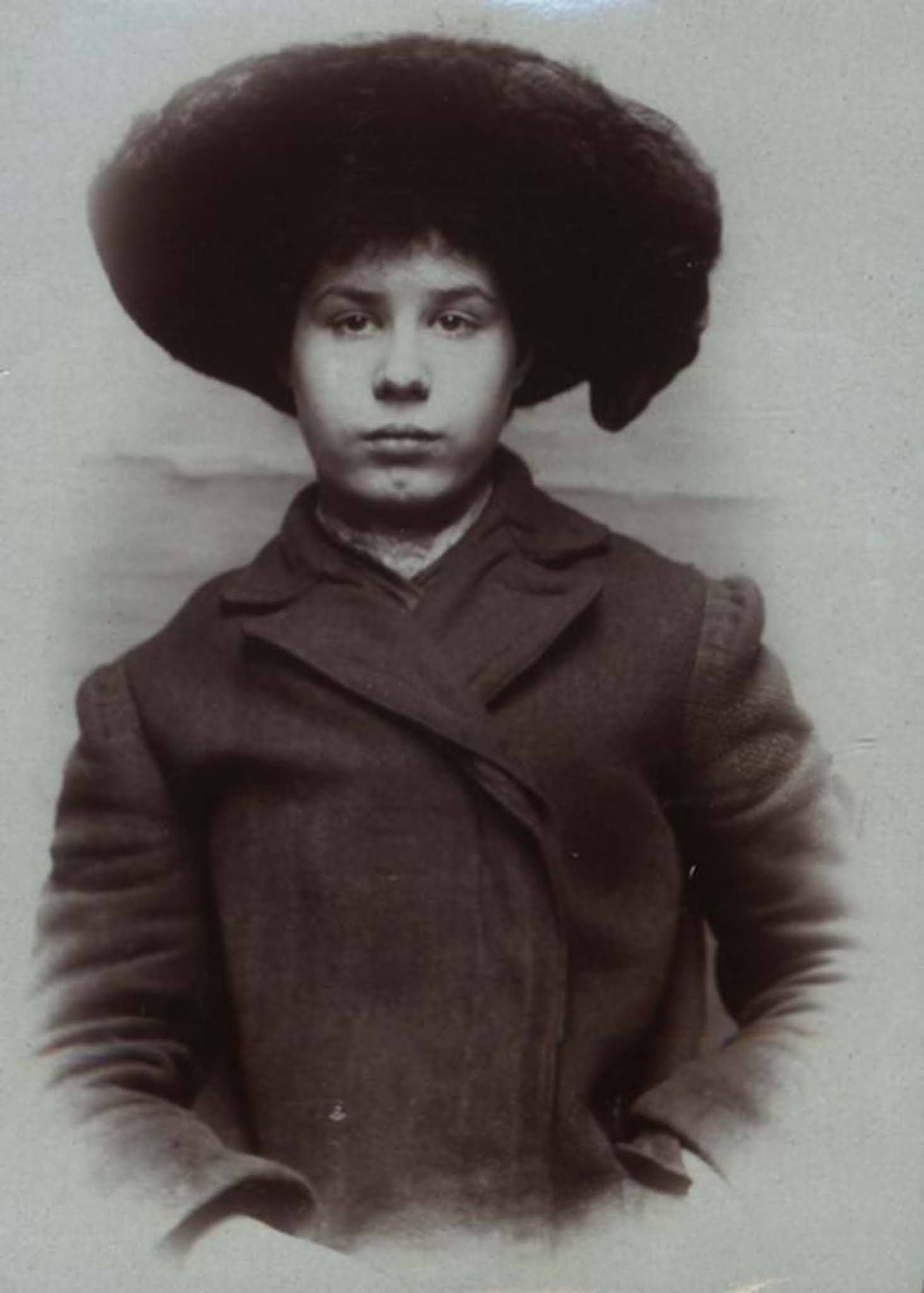

These mugshots of Edwardian Britain depict minors arrested for petty crimes and are part of a wide photographic collection of Tyne Wear Archives.

The age of the subjects starts from 12 years old to 21 which was the legal age of adulthood. These minors were arrested in the British town of North Shields.

By the time Edward VII took the throne in 1901, Victoria had reigned for so long (64 years) that most people couldn’t remember a previous monarch. Her name was synonymous with power, being the figurehead of an empire “on which the sun never sets.”

But the Edwardian age was not really the “long sunlit afternoon” that some have depicted. Edward’s reign began in a period of national uncertainty, and Edwardians faced a period of unsettlement that had its roots in the past. A look at the statistics in the book shows that although Britain was still Europe’s richest nation, others were catching up.

The social issues that had surfaced during Victoria’s reign began to percolate during the Edwardian era. Chief among these was the high poverty rate among the working classes; 77 percent of the population were crowded into the cities, and in many cases wages had actually fallen, although the cost of living continued to grow.

Petty crime, especially among children, had increased sharply at the beginning of the twentieth century. Looking for reasons is not simple, but the short answer has to be the increase in urban poverty as a result of the growing industrial activity.

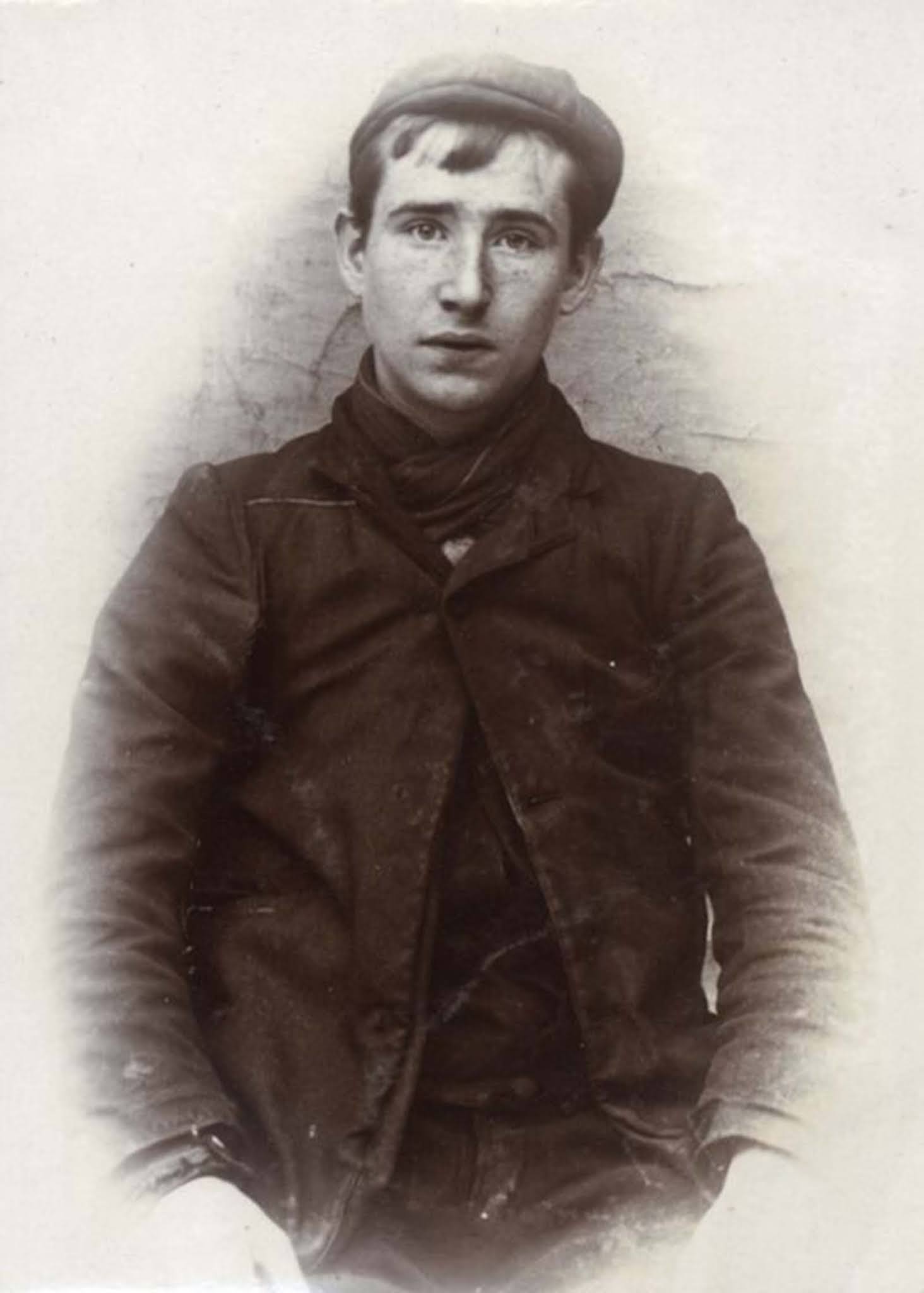

William J. Kay, 18, arrested on suspicion of planning to commit a felony. 1907.

As people poured into the cities in the hope of finding work, so poverty increased and the slums proliferated. The children suffered through violence at home and poverty meant that many skipped school and took to the streets to engage in petty thievery and pickpocketing.

The British legal system introduced different treatments for young offenders from the 1850s onwards when reformatory and industrial schools were first introduced.

In addition to the creation of new punitive measures for dealing with the young, laws were passed removing children from certain areas of industry and restricting their activities in others, while compulsory elementary education was introduced in 1870.

In 1889, the ‘Children’s Charter’ introduced legal protections for children from various types of cruelty and enabled the state to intervene in family life. Efforts snowballed, as campaigners pressed in the 1890s and 1900s for greater legal protection and coverage for children and young people.

These changes were part of a gradual evolution in the concept of childhood, and a growing interest in how the experiences of youth shaped the adult.

These new laws were part of, among other things, an effort to ameliorate the condition of young people by providing them with new opportunities and protections; a growing awareness of the developmental importance of childhood; and of attempts to impose a middle-class conception of childhood upon the working classes.

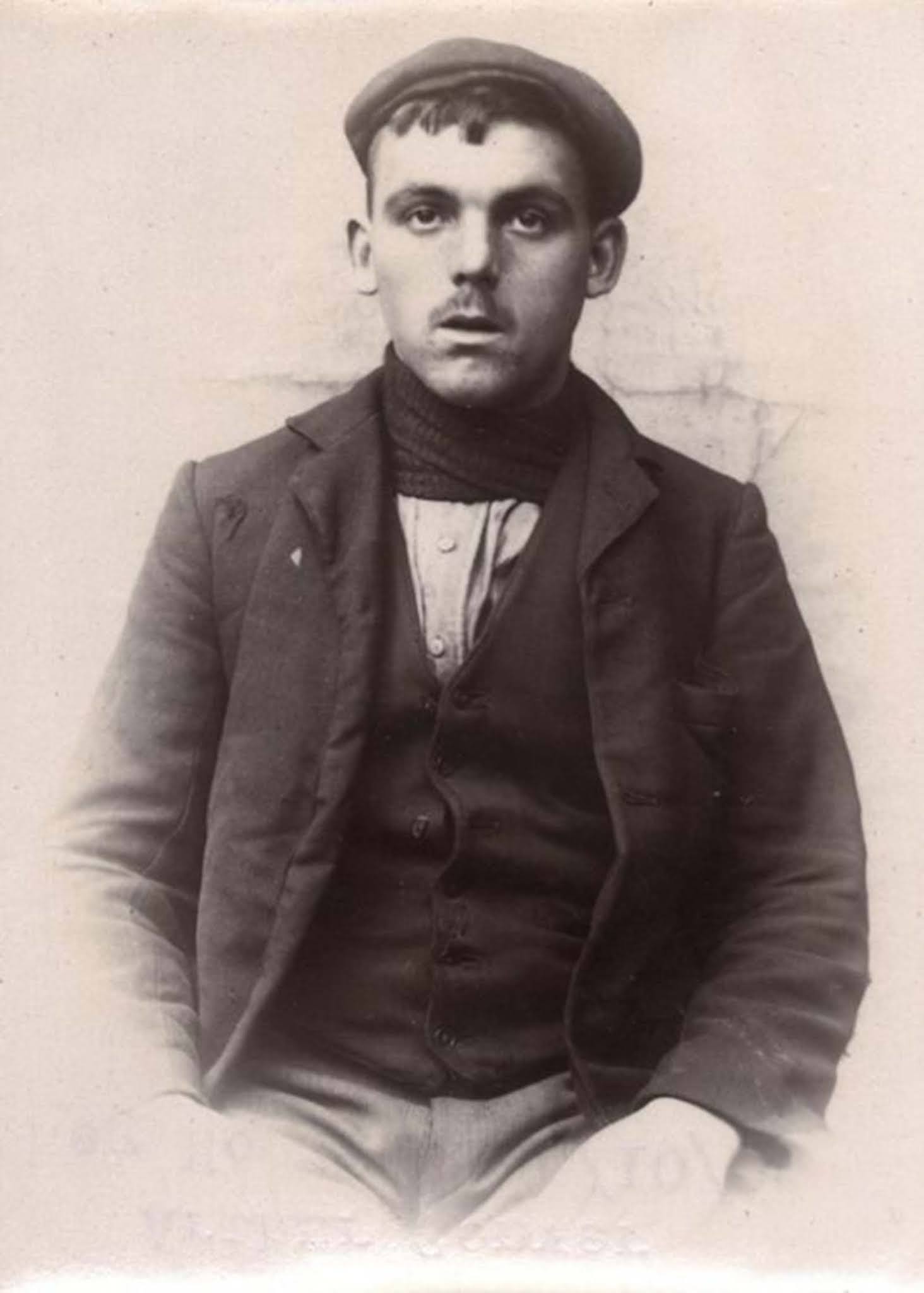

Stephen Fitzgibbon, 17, arrested for a series of thefts. 1907.

Changes in the perception of childhood led to new ideas about the ways in which the delinquent and vulnerable young should be handled by the state.

From the 1880s onwards, campaigners began to call in particular for the introduction of a special court to handle cases involving children and young people.

These efforts finally bore fruit in the Children Act of 1908, one of several reforms of the Liberal Governments of 1906-14, which included the provision of school meals, school medical inspections, and pensions for orphans.

The reformer’s aim was to provide individual treatment for troubled children and to neutralize the impact of poor adult influence. They believed that dysfunctional families were the principal cause of juvenile delinquency.

More specifically, that slum children misbehaved and broke the law because they were not cared for by their parents in ‘appropriate’ ways.

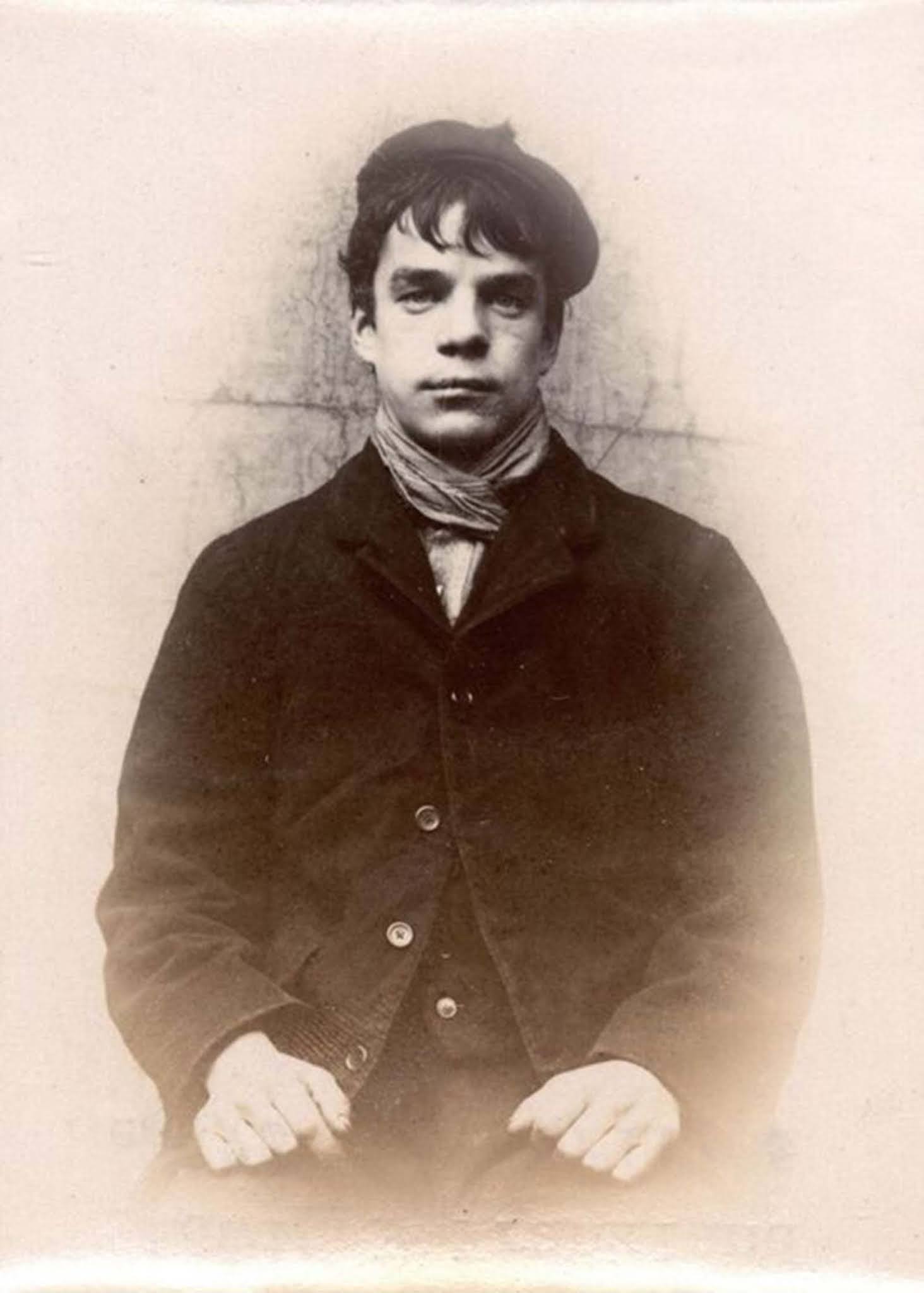

Charles Pearson, 19, arrested for stealing from offices. 1907.

Thomas Pearson, 16, arrested for thefts from backyards. 1907.

Francis Smith, 20, arrested for stealing a copper vessel. 1908.

John Legg, 19, arrested for stealing beer. 1905.

Arthur Convery, 19, arrested for stealing from a gas meter. 1905.

Edwin Frankland, 17, arrested for breaking into a house. 1905.

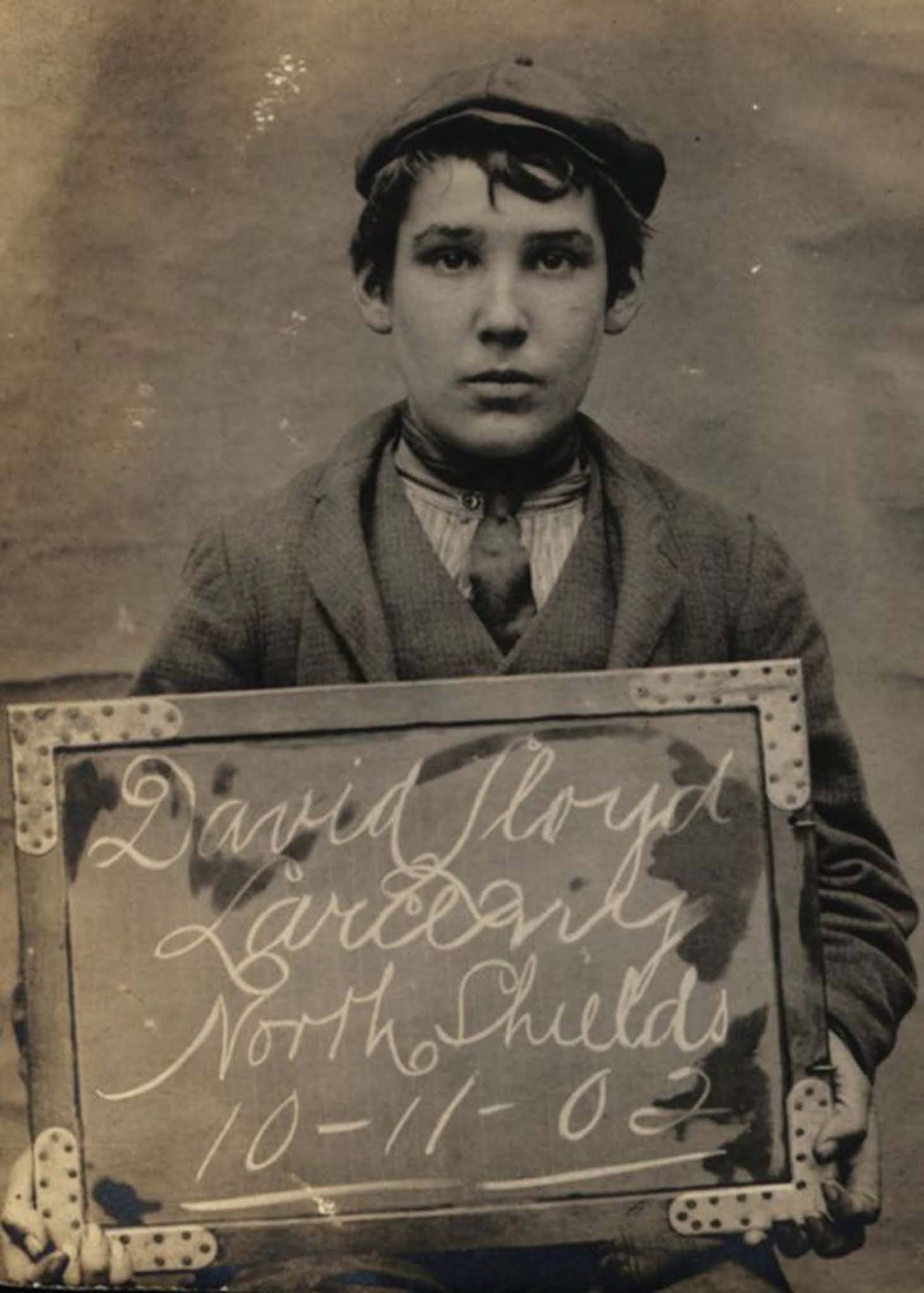

David Lloyd, 15, arrested for stealing brushes and a box. 1902.

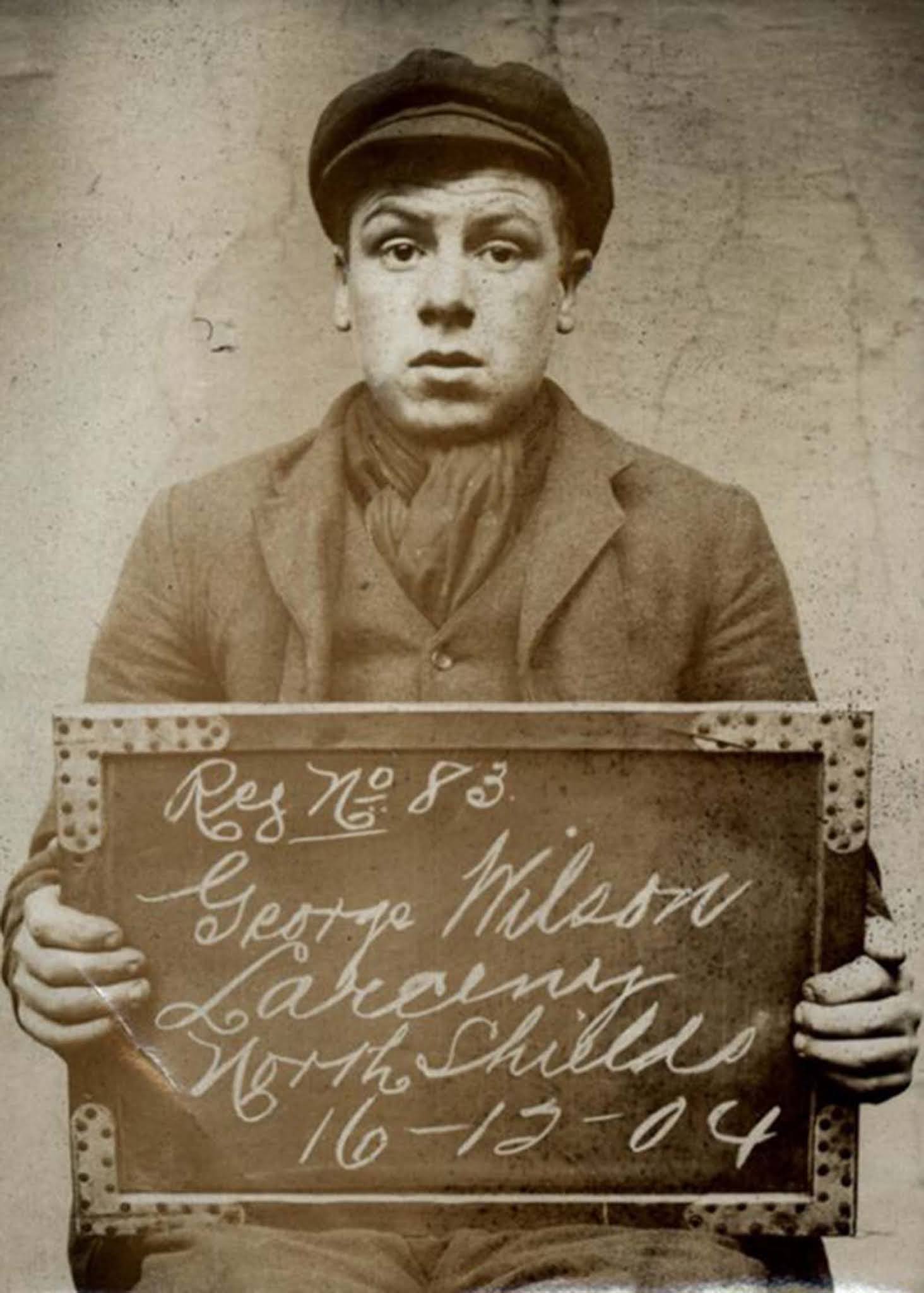

George Wilson, 17, arrested for stealing from his father. 1907.

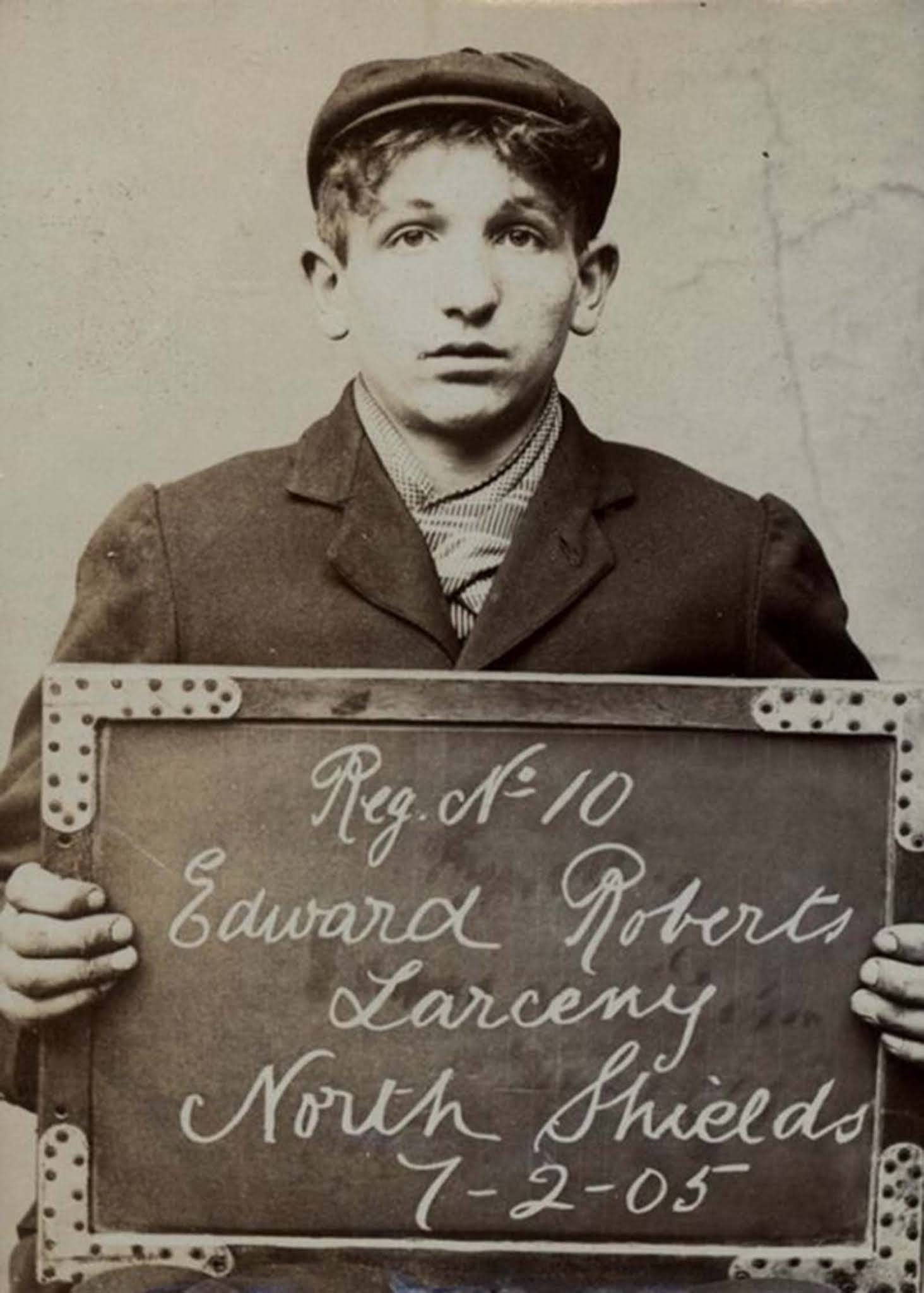

Edward Roberts, 19, arrested for stealing from a gas meter. 1905.

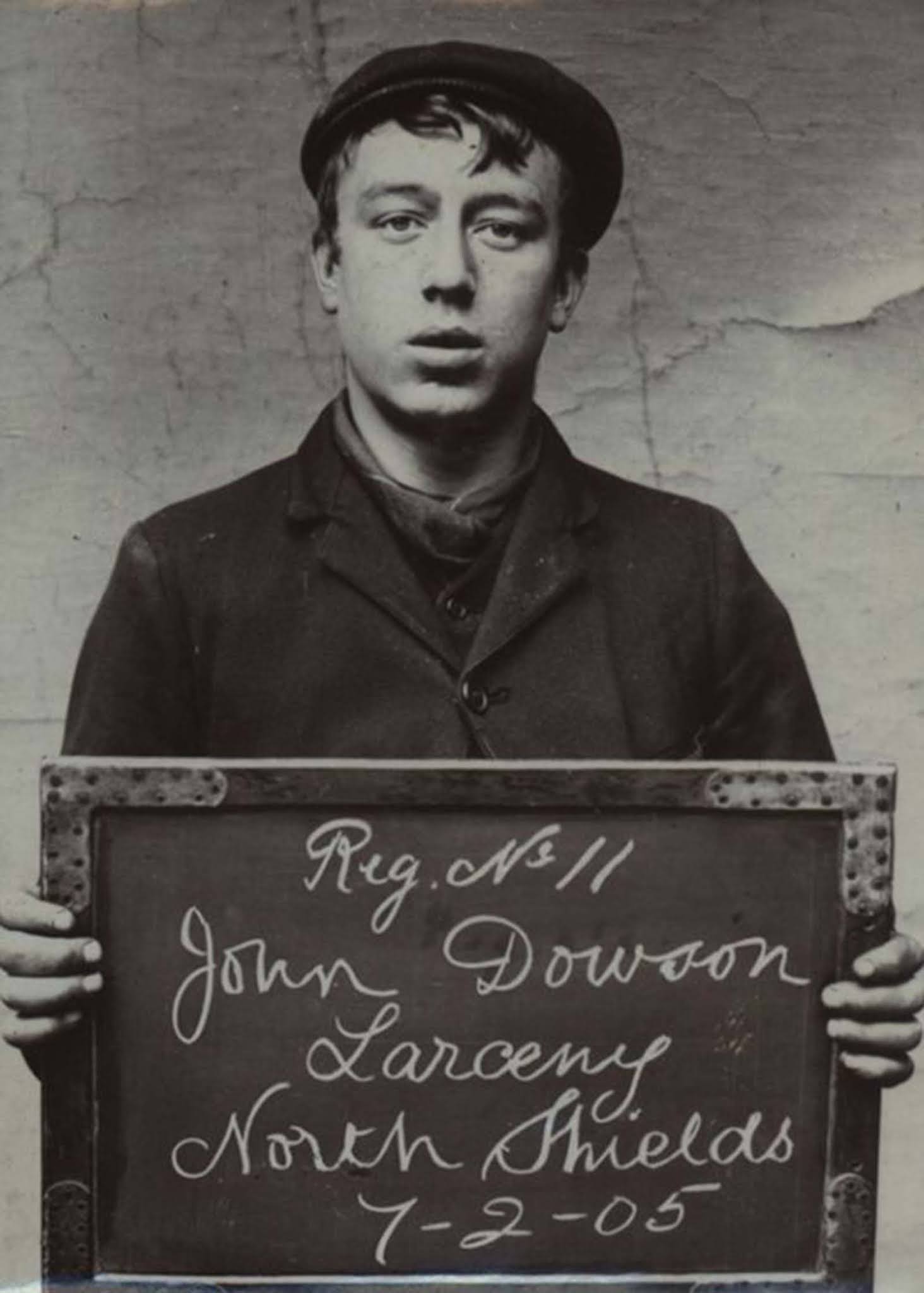

John Dowson, 19, arrested for stealing from a gas meter. 1905.

George Herbert Morton, 17, arrested for theft. 1906.

Percy John Proctor, 16, arrested for fraud. 1906.

George Thompson, 17, arrested for stealing from a ship chandler’s store. 1903.

John Fatherley, 16, arrested for stealing from a ship chandler’s store. 1903.

Charles Marr, 14, arrested for an undisclosed reason. 1906.

John Scott, age unspecified, arrested for stealing from a shop door. 1906.

Thomas Wallace, 18, arrested for indecent exposure. 1905.

Benjamin McMurdo, 15, arrested for breaking into shops. 1905.

William Balmer, 15, arrested for shopbreaking. 1902.

George Burn, 14, arrested for stealing brushes and a box. 1902.

Dora Agnes Sanderson, 16, arrested for theft. 1906.

Alice Maud Marr, 17, arrested for stealing doormats. 1907.

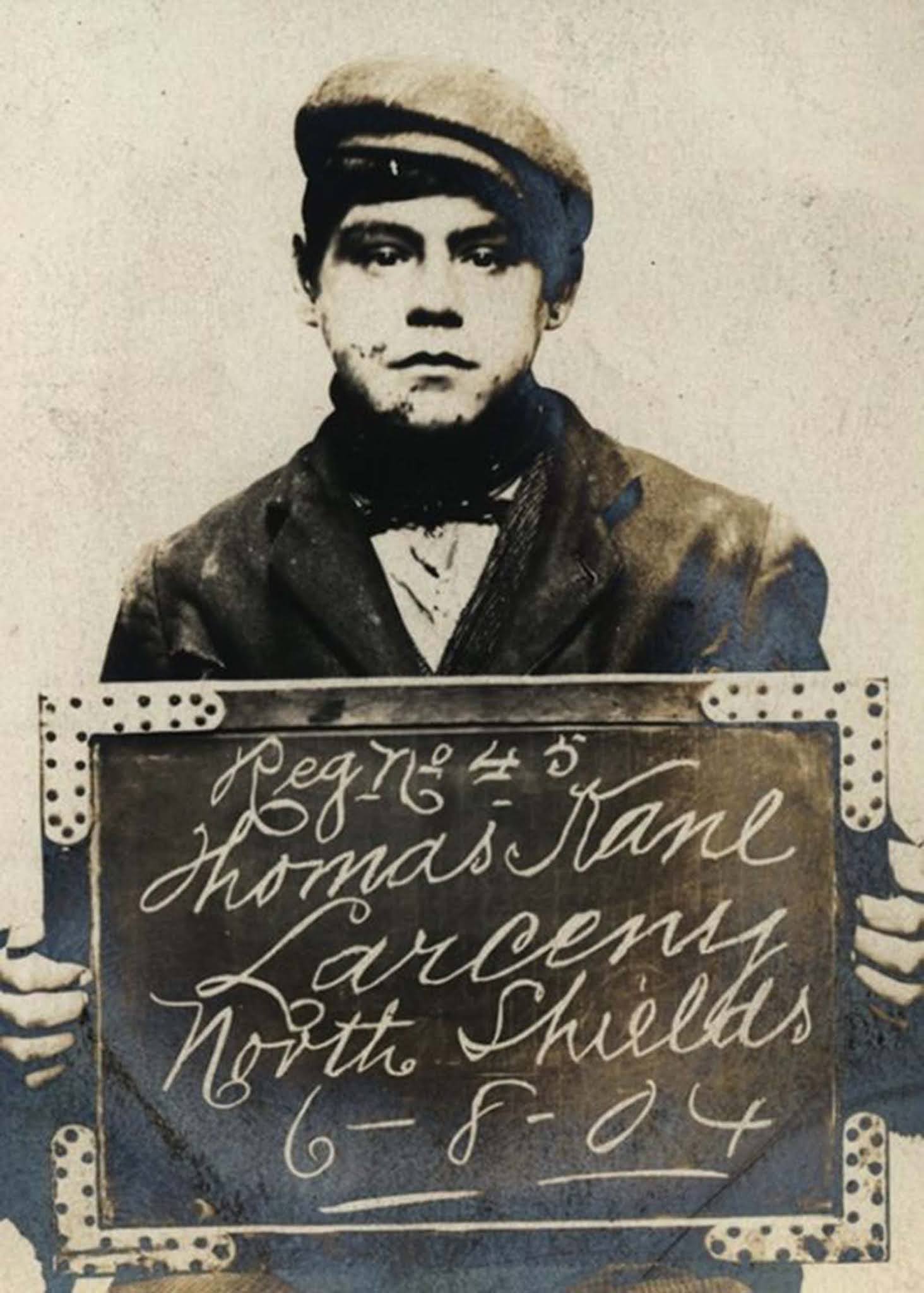

Thomas Kane, 16, arrested for stealing a pony, harness, and cart. 1904.

Gilbert Wheatley, 19, arrested for loitering with intent to commit a felony. 1904.

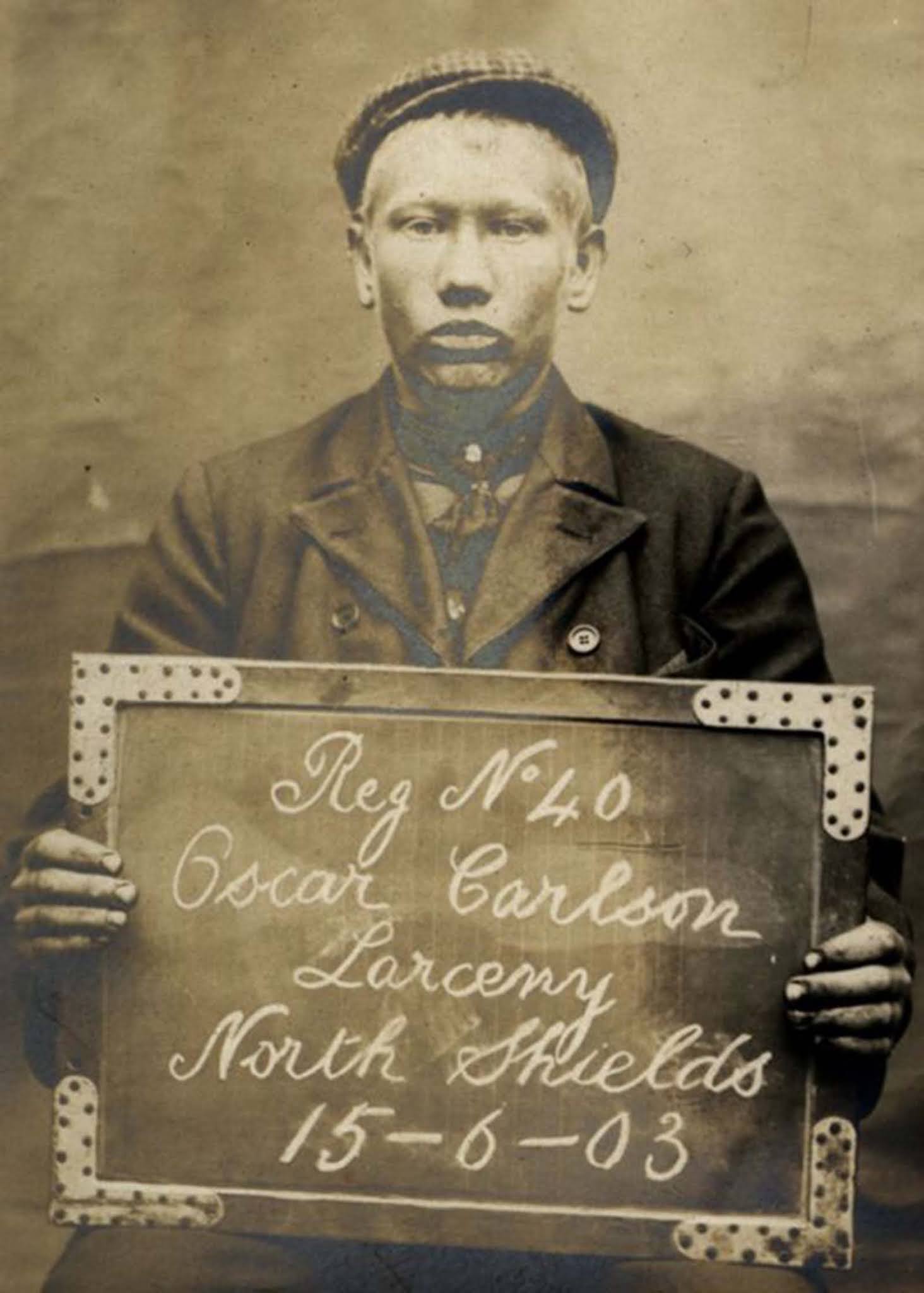

Oscar Carlson, age unknown, arrested for theft. 1903.

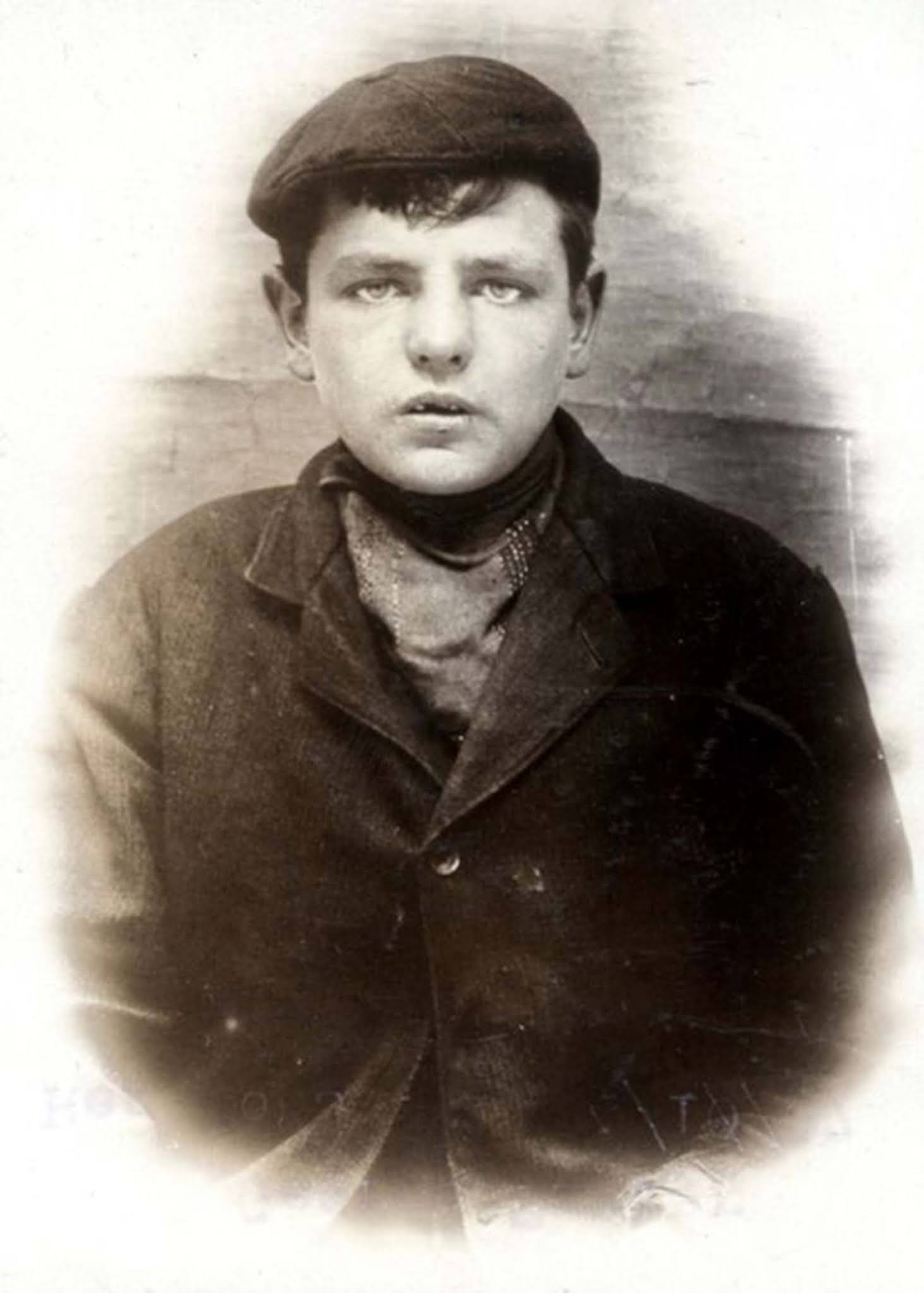

William Wadham, age unknown, arrested for sleeping outdoors. 1904.

George Taylor, 17, arrested on suspicion of planning to commit a felony. 1907.

Percy Swallow, 16, arrested for stealing a watch. 1907.

Margaret Leadbitter, 12, arrested for stealing money from other children. 1904.

Margaret Ann O’Brien, 14, arrested for obtaining money by false pretenses. 1904.

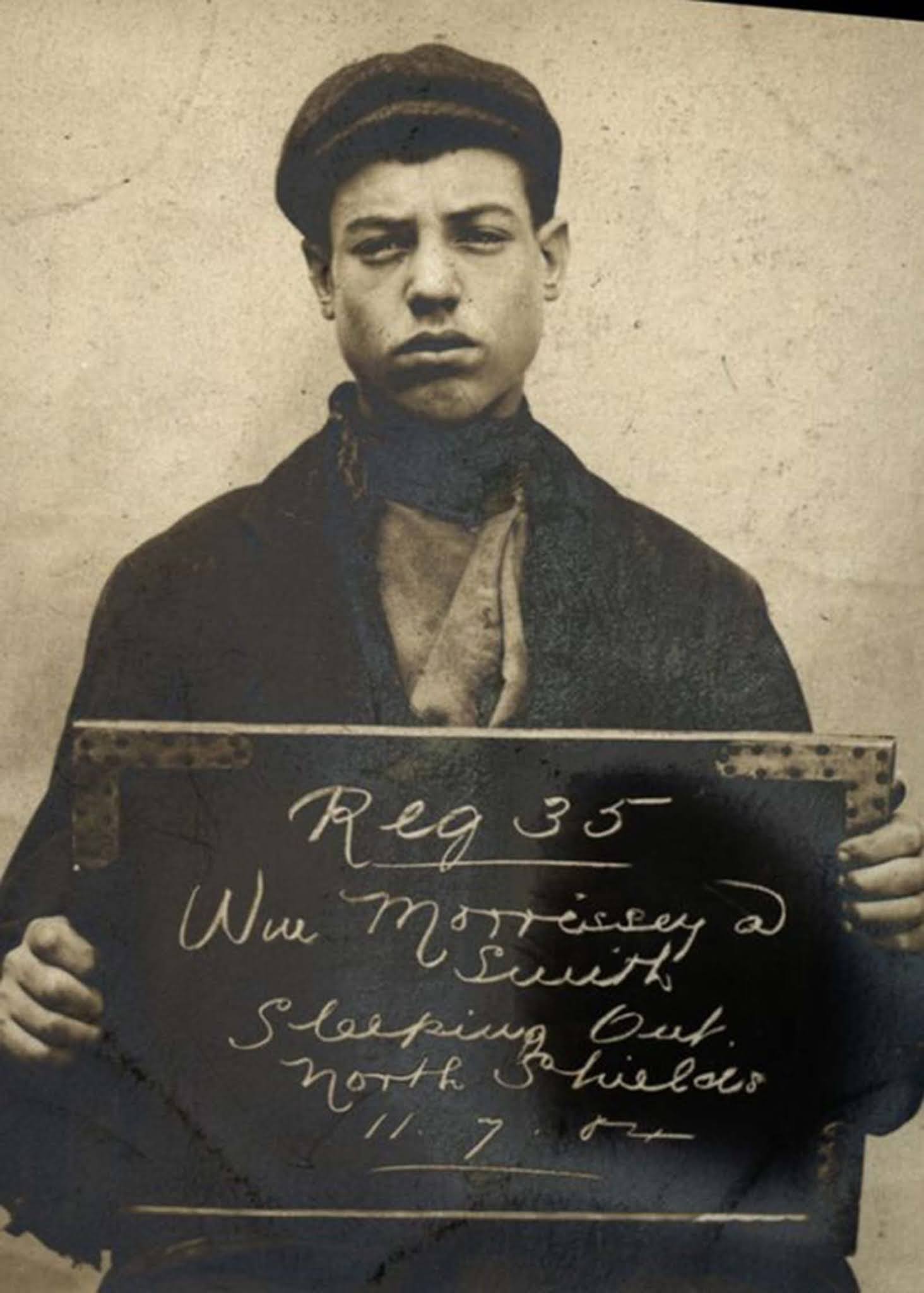

William Morrissey, age unknown, arrested for sleeping outdoors. 1904.

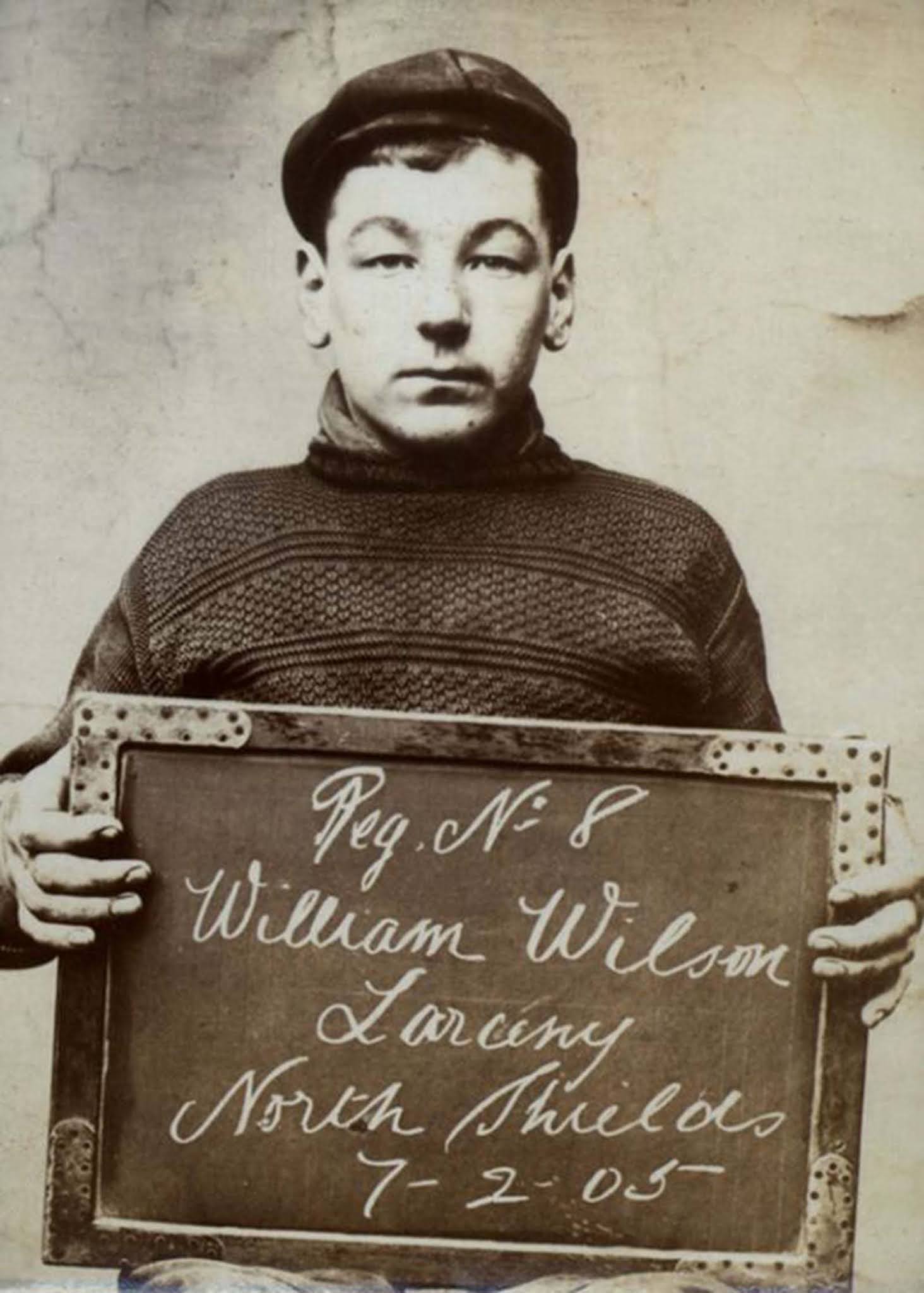

William Wilson, 16, arrested for stealing fish. 1905.

Robert Richardson, 18, arrested for breaking and entering. 1907.

Sidney Forrest, 17, arrested for stealing a pair of reins and two whips. 1908.

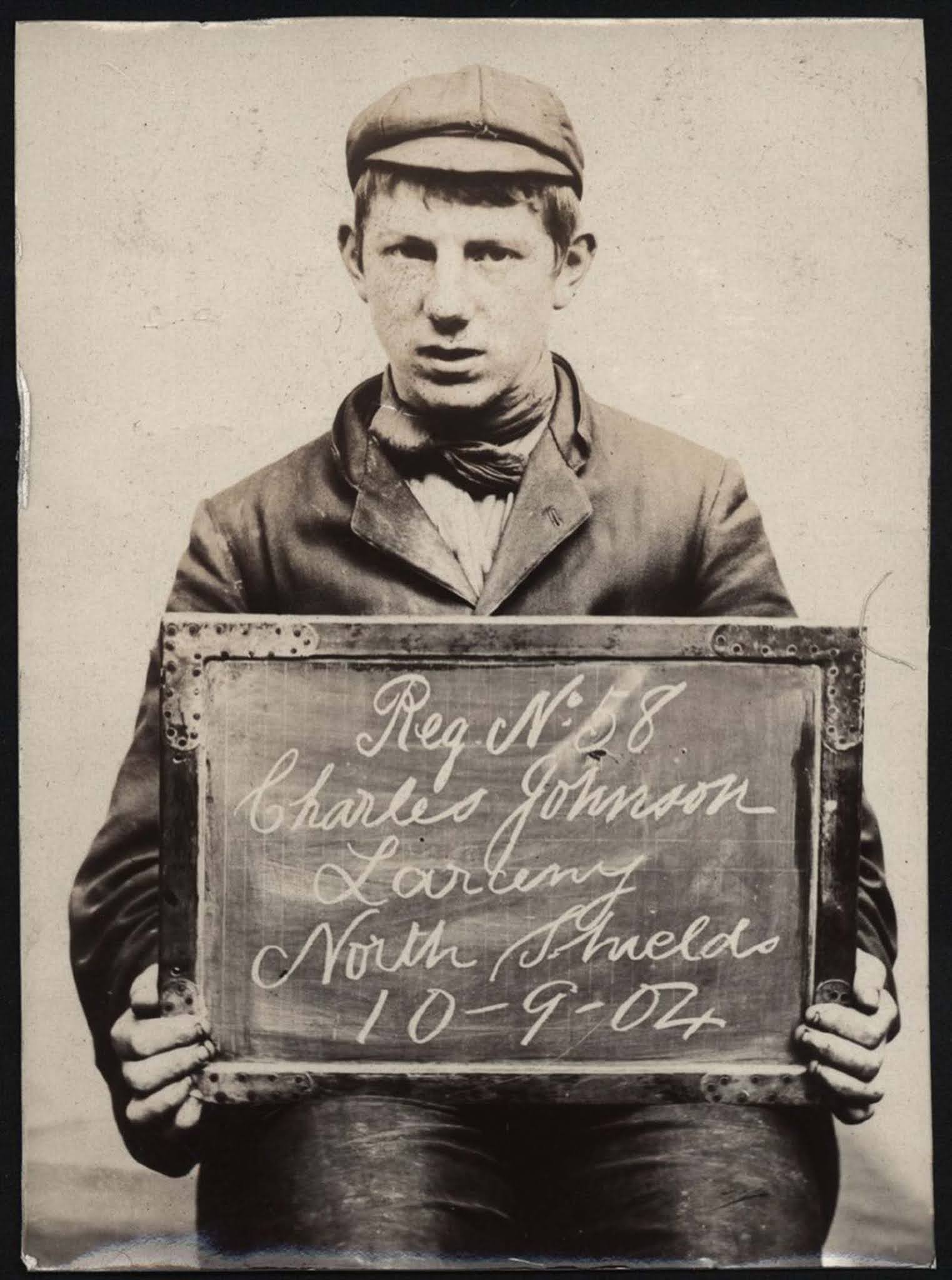

Charles Johnson, age unknown, arrested for stealing sash weights. 1904.